Last-mile distribution in the pandemic

How did the pandemic affect e-commerce operations? Understanding resilience in the context of last-mile distribution sustainability.

On 11th March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the novel coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic. The days thereafter saw governments around the world establish contingency plans with lock-downs announced to contain the spread of virus. This ushered a frenzy of purchase and hoarding of daily essentials leading to supply shortage at local brick and mortar stores. However, the fear of virus contraction also made shopping in-store inconvenient and stressful. This nudged many consumers to shop online instead, leading to a significant rise in e-commerce demand, particularly for specific range of products. While e-retailers design their operations to absorb variations in demand which are typically high-probability low-severity fluctuations (such as holiday season demand), this surge in demand, a low-probability high-severity fluctuation, gave little time to the e-retailer to re-organize and re-evaluate its operations. Thus, to cater to this unprecedented surge in demand, e-retailers had to scale up their operations constrained to pre-pandemic level of resources, thereby operating at a lower level of service with high lead times, delivery failures and demand prioritization. This pandemic thus motivates research in developing resilient last-mile distribution that can resist, absorb, and recover from such low-probability high severity disruptive events.

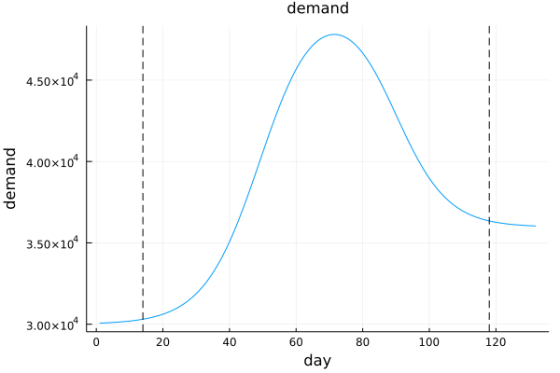

Demand surge during the pandemic

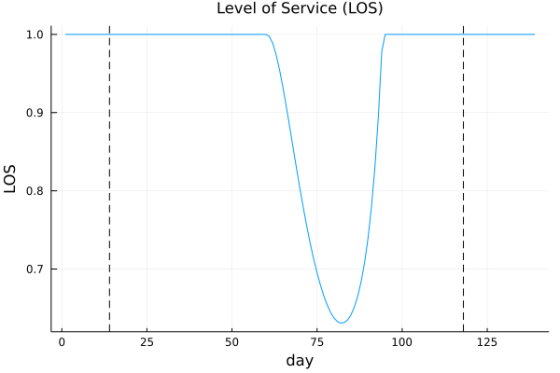

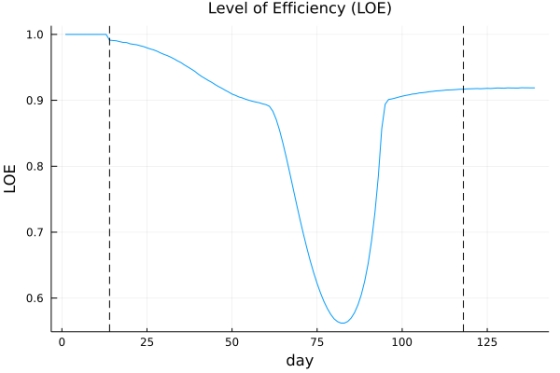

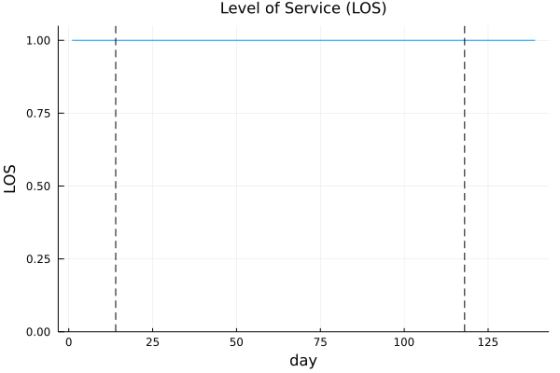

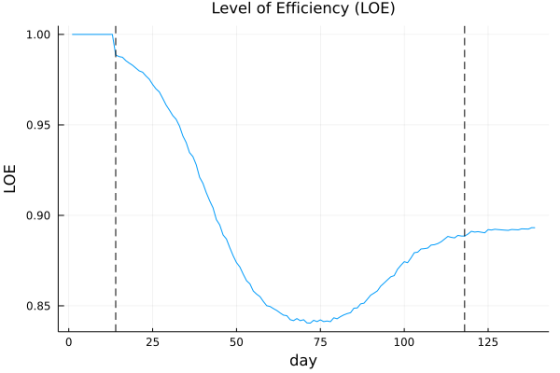

The two vertical dashed line represent disruption start (day 18) and disruption end (day 114)

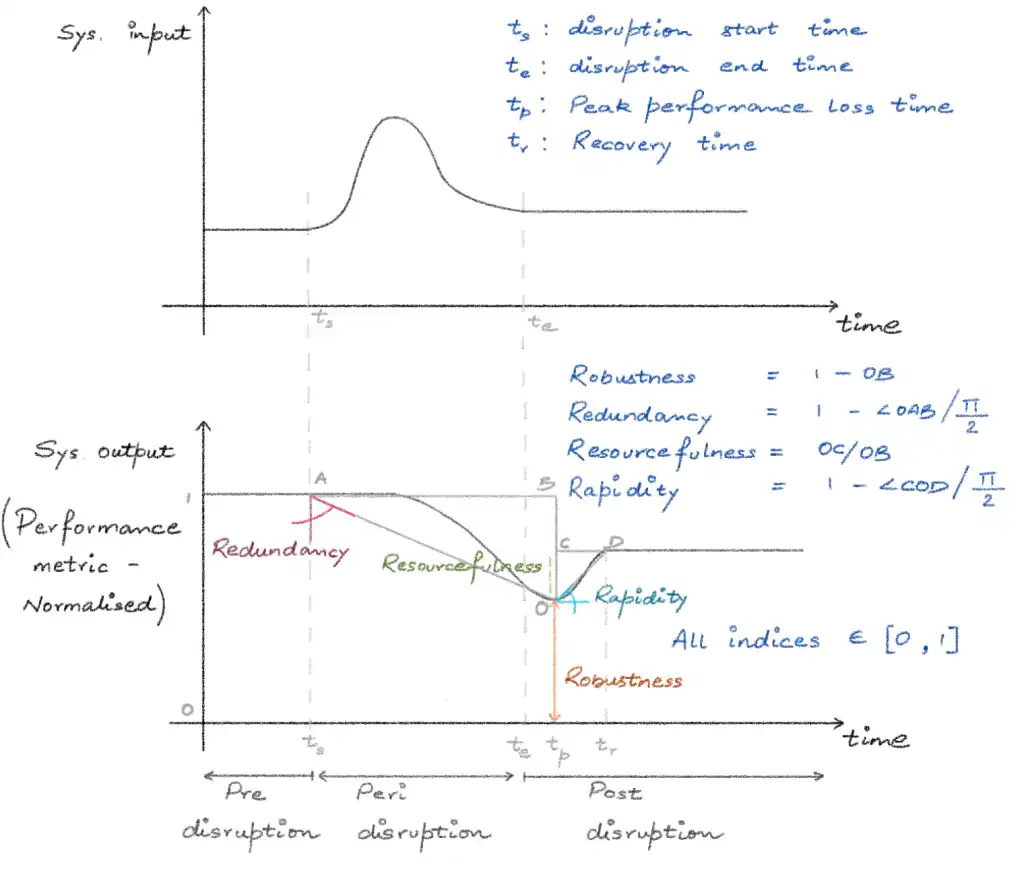

Before we begin our discussion on resilient distribution, let’s take a look at a dictionary-esque definition of resilience. Resilience – a term common to disaster management, is the ability of social units to mitigate hazard, contain the effects of disaster when they occur, carry out recovery activities in ways that minimize social disruption, and mitigate the effects of future disaster. Typically, when a system is exposed to a disruption, its performance metrics fall, then plateau, before recovering back to a certain extent (as shown in the figure below). This system response is modeled and quantified using resilience triangles in conjunction with the R4 framework. The R4 framework formalizes the dictionary definition of resilience into four attributes of resilience, namely, Robustness (ability to absorb), Redundancy (ability to substitute for disrupted elements within the system), Resourcefulness (ability to diagnose and initiate solution), and Rapidity (ability to recover timely). The resilience triangles quantify these attributes for tangible and meaningful analysis of system’s response to disruption (see figure below). In particular, 1) Robustness is defined as the height of the performance curve at peak performance loss, 2) Redundancy is quantified as the average rate of performance decay, 3) Resourcefulness metric represents the ratio of recovered performance to peak loss, and 4) Rapidity, like Redundancy, identifies the average rate of recovery. The disruption, system’s response, and the four metrics are detailed in the figure below.

Modeling system’s response to disruption using resilience triangles and the R4 framework

Case Study

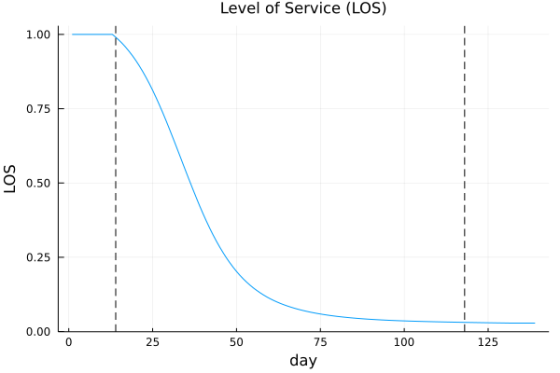

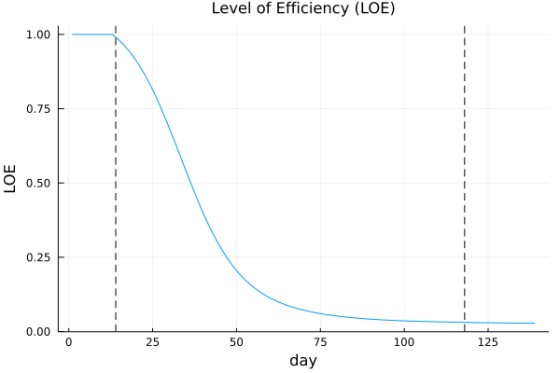

In the context of last-mile distribution, this work defines resilience as the ability of the e-retailer to maintain satisfactory level of freight flow in the event of disruption, and recover efficiently with minimal use of resources – time, capital, and human effort. Based on the above discussion, this study introduces two performance metrics – a Level of Service (LOS) metric representing the ratio of served to total demand, and a Level of Efficiency (LOE) metric representing ratio of cost of operating under normal conditions to the cost of operating under disruption. Notice, these metrics are consistent with definition of resilience introduced in the context of last-mile distribution. The former identifies level of freight flow while the latter represents use of resources. Prior to the disruption, this work assumes operations of an e-retailer serving 30000 customers located randomly and uniformly in a service region of size 475 sq. mi., using diesel trucks from an e-commerce fulfillment facility. Given a time-horizon of 10 years and 9 working hours in a day, the objective of the e-retailer is to optimize its strategic and tactical operations so as to minimize the total cost of last-mile delivery. Such a design of last-mile distribution structure is consistent with the lean management principles of supply-chain design. In the event of a disruption, the e-retailer observes a demand shock (peak demand of 47,500 customers). Due to lean design of the last-mile distribution structure, e-retailer has no redundant capacity. Thus, to meet daily demand, e-retailer has to outsource the demand over capacity, which this work describes as surge-outsourcing. This outsourcing channel can be crowdsourced drivers crowd-shipping delivery, or a 3rd party delivery service provider. Any unmet demand above the capacity of the combined distribution structure is served the next day. This work penalizes the e-retailer for this unmet demand. Post-disruption, the e-retailer again observes a stable level of demand – 36000, and thus re-optimizes its operations so as to minimize the total cost of last-mile delivery.

To evaluate delivery tour length and travel time, establish customers served per delivery tour, number of tours per delivery vehicles, fleet size, and associated fixed, operation and emission cost, a last-mile distribution model is developed using Continuous Approximation (CA) methods.

Below are the LOS and LOE performance curves, and related resilience metrics for the three scenarios, 1) no surge-outsourcing (None), 2) surge-outsourcing via crowd-shipped drivers (Crowd-shipping), and 3) surge-outsourcing via 3rd party carrier (Outsourcing).

Level of Service (LOS) and Efficiency (LOE) without any surge-outsourcing

Level of Service (LOS) and Efficiency (LOE) with crowd-shipping

Level of Service (LOS) and Efficiency (LOE) with delivery outsourcing (3rd party delivery service provider)

In operations research, and in general in systems design, the prime objective is to develop an economically viable and a socially equitable system with minimal externalities (three fundamental pillars of sustainability). However, certain systems and environments may be exposed uncertain elements, such as daily demand, traffic speeds, etc. for a last-mile delivery distribution system. Such stochastic systems are designed with additional investments and protections so as to minimize the likelihood of failure. However, a more robust, and a more sustainable system can be developed by embracing resilience as one of the fundamental pillars of sustainability. The above developed framework aids in quantifying resilience in the form of system’s ability to absorb consequences of disruption (Robustness), system’s ability to replace affected elements in the event of a disruption (Redundancy), system’s ability to initiate solutions toward recovery with minimal use of resources (Resourcefulness), and system’s ability to recover timely (Rapidity). The benefits of designing not only sustainable but resilient system can be evidenced from the case study developed in this work. Under normal working conditions, e-retailer benefits from owning a fleet of diesel trucks and keeping delivery operations in-house as it allows efficient consolidation and operations. The total cost per package to serve pre-disruption demand (30,000 customers) turns out to be $1.68 when the e-retailer deploys its own fleet, $2.38 when the all the packages are instead crowd-shipped, and $2.64 if the e-retailer decides to outsource delivery via a 3rd party carrier. However, to be able to surge-outsource part of its operations in case of disruption (be it low-probability high-severity or high-probability low-severity) allows for a more resilient distribution structure, as can be seen from the figures above. This shows that a “sustainable” system may not be resilient (and also vice-versa, though this is of less significance), and that there may be a tradeoff between “sustainability” and resilience, or in case of last-mile distribution, there may be a tradeoff between designing lean vs. resilient system, thus bolstering the argument for embracing resilience in sustainable design.

Enjoy Reading This Article?

Here are some more articles you might like to read next: